EULA for Android

Android apps are not required by Google Play to include an End User License Agreement ("EULA").

However, having an EULA in place regardless can be a good thing for a number of reasons, including protecting your intellectual property, and limiting your liability to users of your app.

While using the Apple platform comes with a ready default End User License Agreement (EULA), you will not enjoy that same advantage with the Android marketplace from Google or Amazon.

Google Play Store and Amazon App Store offer distribution agreements that do not cover your proprietary interests of your Android app.

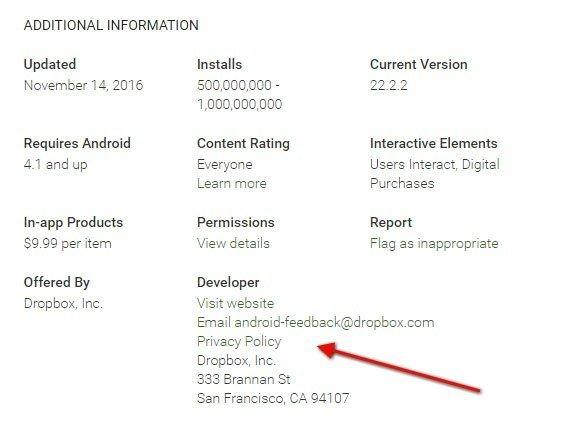

Here's an overview of these default provisions and how to start on an EULA that will protect your Android apps.

EULA for Android apps

You want an EULA for the same reason you would draft Terms & Conditions (T&C) or Terms of Service or Terms of Use: it's a tool that protects your interests and gives a heads-up to users on what to expect.

What is a EULA

An EULA is a contract between you and the user who purchases your software - your Android app. It gives the user the right to download your app and use that copy of your app after they submit payment (if applicable).

The EULA works the same for apps which download onto a device for the benefit of the user. If the majority of resources needed to run the software depend on the user's device or computer, you will prefer having an EULA. That is due to the fact that allowing these copies often leaves your company vulnerable to infringement.

A EULA agreement will often address:

- The scope of the license

- App fees and purchase price

- And limitations on liability

You will also want provisions regarding termination of the license and intellectual property information including copyrights, trademarks, and restrictions on use.

Why use EULA for Android apps

When you allow a user to download your app for use, you are taking a calculated risk. A user with that access could reverse-engineer the app and recreate it as their own.

Without the protection of the EULA agreement, you may lack remedies if the user modifies the code of the app and then distributes the modified app for profit - and without attributing to you or your company.

Google Play Store

Developers that are submitted their Android apps on Google Play Store without their own EULA agreements are subject to these broad and general terms listed in the "Google Play Developer Distribution Agreement" (available on this page).

In that agreement between you (the developer) and Google Play, you are allowed to create a separate EULA specific to your app as long as it does not conflict with the distribution agreement:

Because the EULA agreement isn't a requirement by Google for Android apps available on Google Play, many apps don't have this legal agreement.

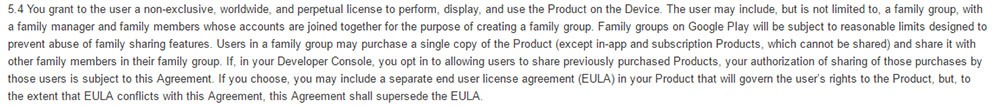

Facebook's Android app page on Google Play includes a Privacy Policy link, but there's no link to the EULA agreement:

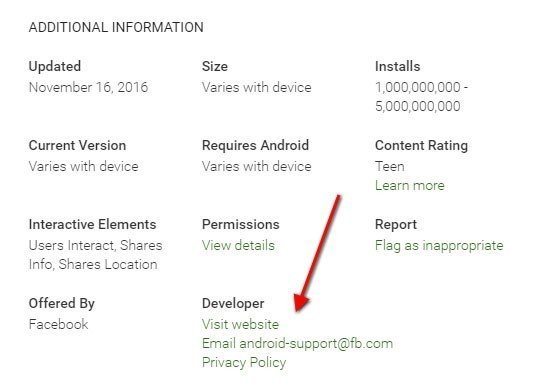

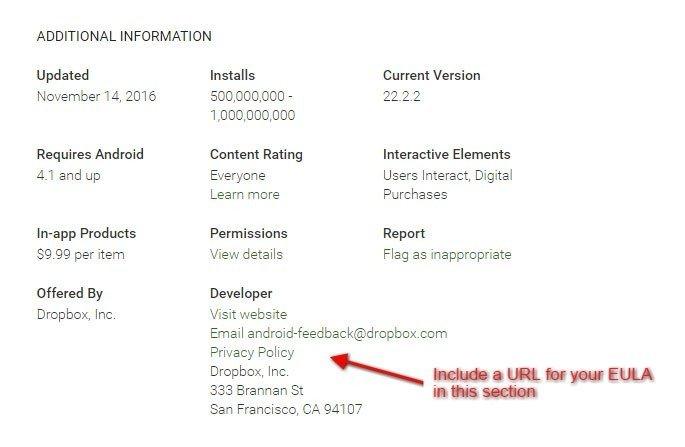

Similarly, the Dropbox Android app page includes a Privacy Policy agreement, but no EULA agreement:

Because neither of these apps include an EULA, the Android Market Terms of Service agreement will be the binding agreement between the Android app and the users using the app.

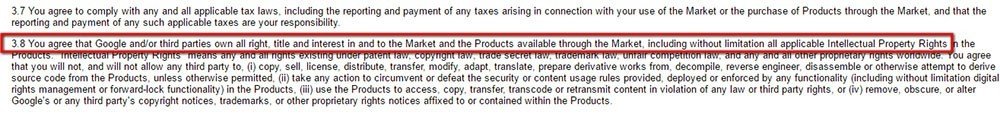

The Android Market Terms of Service includes many useful clauses, including protection for your intellectual property rights as a developer and a disclaimer of all warranties:

However, not all potential issues are addressed in the Android Market Terms of Service agreement.

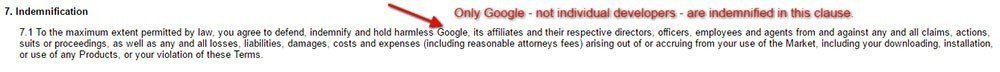

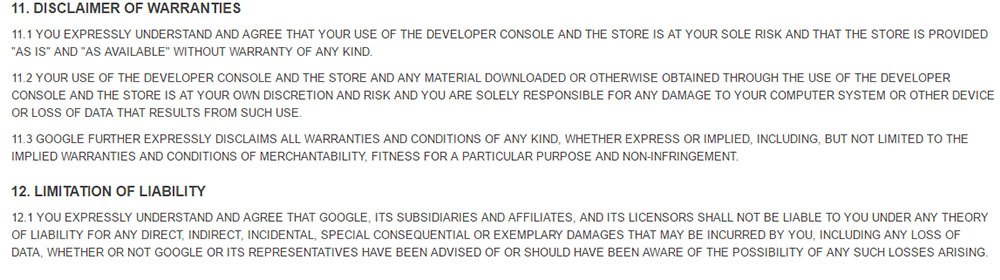

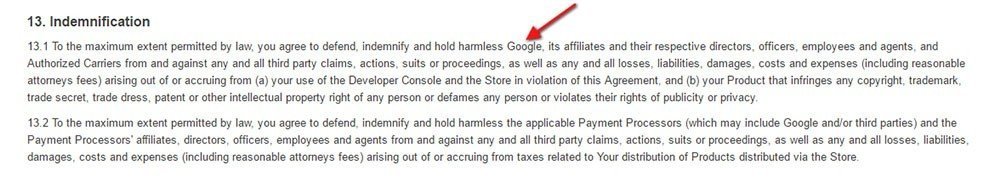

For example, Google includes a clause that limits its own liability, as well as an indemnification clause, but you will not have your liability limited, nor will you be indemnified under the Android Market Terms of Service:

To fully protect yourself and your app, you should consider including an EULA with your Android app even though it isn't required. This will help to patch the holes in the default Android Market Terms agreement.

Amazon Appstore

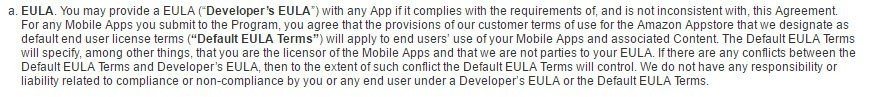

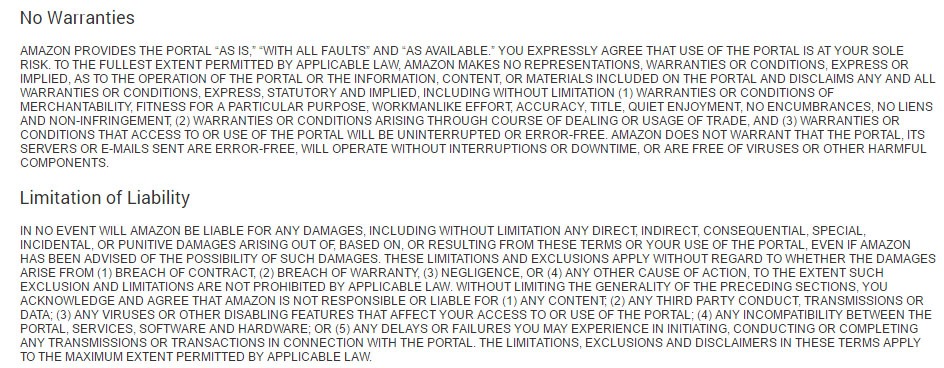

The "Amazon Appstore Distribution and Services Portal Terms of Use" page contains a similar provision:

Clauses in EULA for Android apps

Include these sections for an effective EULA agreement to protect your Android app.

Scope of license clauses

The scope of the license granted by the EULA agreement can include:

- Authorized uses

- Limits on software copies or devices where the app is installed

- And whether users have the option to modify the code

The temptation may be to only grant the user authorization to "just use" the software. However, since that is a broad term that could include reverse-engineering with some people, you need to be specific.

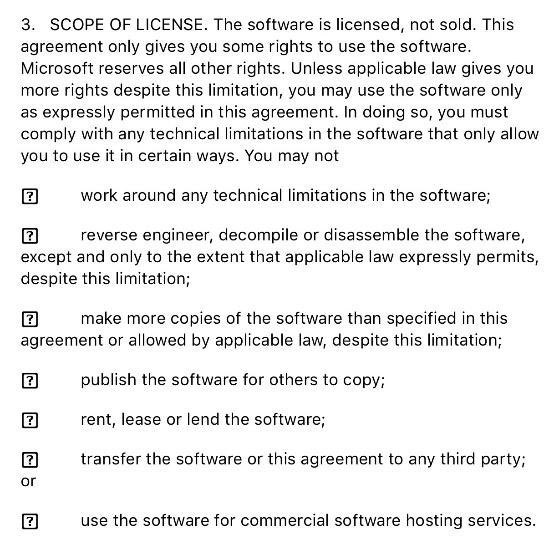

For Office 365, Microsoft offers a very detailed scope of license section. While this example is for its iOS app, not the Android app, it shows the extent you must take to describe authorizations and limitations to a user:

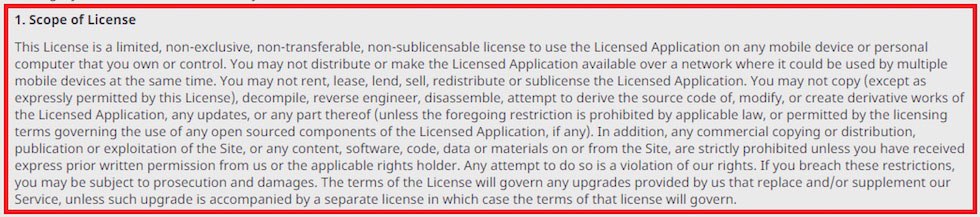

The Viber app allows for users to make free calls and use quality video. It contains many of the same restrictions on copying and reverse-engineering its app. These limitations are stated at the beginning of the agreement:

If your list of restrictions is particularly long, you will likely want to go with the bulleted list, like Microsoft does above. That assures there are no doubts as to the scope of your app.

More general and ordinary restrictions, like those adopted by Vibber, can get away with paragraph form and bypass the bullets.

Licensing fees clauses

If a user must pay the fee before downloading your app, you can often get away with not having a paragraph devoted to payment in your EULA. However, if there's a monthly subscription fee required to maintain usage rights, you will need to include that.

These terms should be within the Terms & Conditions or Terms of Use agreement. However, repeating them in your EULA is not a bad practice. Just double-check to make sure the terms are consistent in each agreement.

Warranties, disclaimers and limitations on liability clauses

There's always a risk when you distribute your mobile apps.

Warranties, disclaimers, and limitations of liability in the Google Play distribution agreement apply to your relationship with them as a developer. There's no content that controls warranties between you and the user:

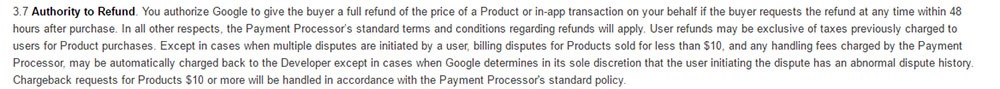

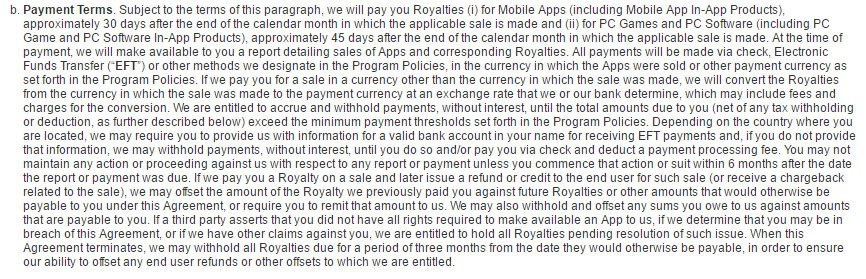

However, Google maintains a right to issue refunds if a user is unsatisfied with your app. It does not appear that developers have a right to dispute this process:

The same is true with the Amazon Appstore. Just as with Google, they waive warranties and limit liability as it relates to the relationship they have with developers. These provisions do not apply to users:

Refunds are also within Amazon's discretion without your input. Plus, they maintain a right to count those refunds against any balance owing to you for app purchases:

If you are concerned about liability and being held to warranties that should not be relevant, you certainly must create your own EULA.

In the case of Parallels Software, they add these clauses:

By not having your own EULA, you risk taking on warranties and performance guarantees that could prove more than your app can handle.

A separate EULA agreement is the only way to assure that you effectively limit liability.

Termination of license clauses

Grounds to terminate the license could include:

- Nonpayment

- Inappropriate use

- Or violations of the agreement

If you enter the Android marketplace without your own EULA agreement, you risk having no cause to terminate a license when the situation arises.

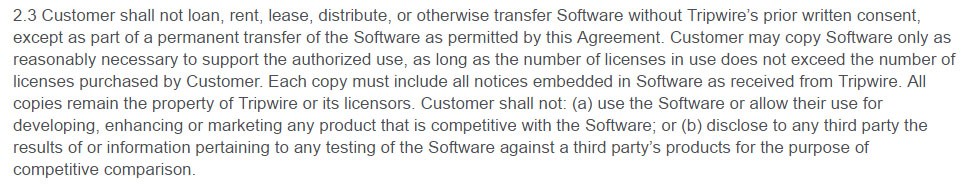

Tripwire takes a broad approach by stating that violating the EULA will result in termination of the license. It also offers a way to terminate the license voluntarily through writing:

Parallels Software also provides similar terms along with a reminder that using the software assumes the acceptance of the EULA agreement's terms:

Even stating broad termination conditions is helpful. It allows you to end the license if a user modifies the code or distributes your app without authorization.

This can prove vital when it comes to protecting your intellectual property rights, which also need to be outlined clearly in an EULA agreement.

Intellectual property ownership and limitations clauses

Intellectual property concerns the copyrights, trademarks, and restrictions on modification, copies, and distribution.

If you have a closed-source proprietary app, the EULA agreement gives you cause to terminate a license if a user starts changing it or selling the modified code of your app for profit.

Even in open-source software packages, you likely have limitations that prevent distribution for profit or using the code without attribution.

Tripwire starts its section on licensing and ownership by explaining these interests:

After making that clear, it moves on to explain restrictions, including those on distribution and copies:

Indemnification clauses

While the default Google Play Developer Distribution Agreement includes an indemnification clause, only Google is protected under it, and not you as a developer.

To make sure you're also protected, include an Indemnification clause in your EULA.

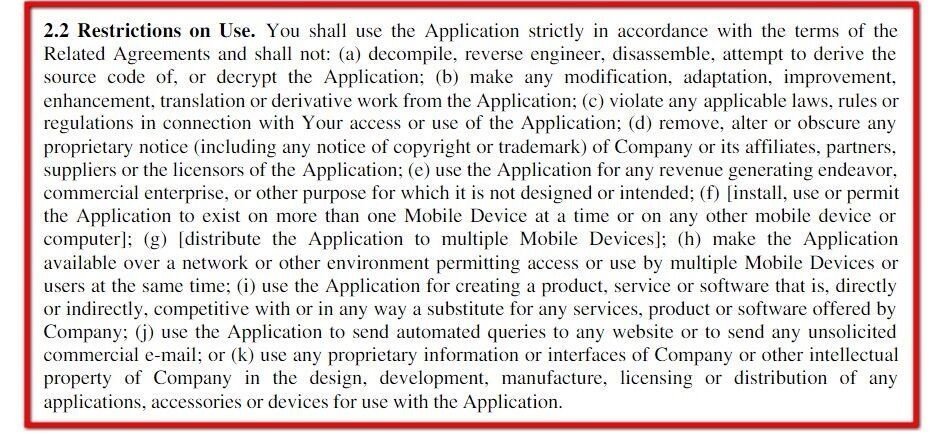

Restrictions on Use clauses

Vimeo's EULA agreement includes a section for "Restrictions on Use" of its app.

Here's where Vimeo users are told how they're not allowed to use the app. This protects Vimeo from abuses and provides a way for Vimeo to enforce restrictions.

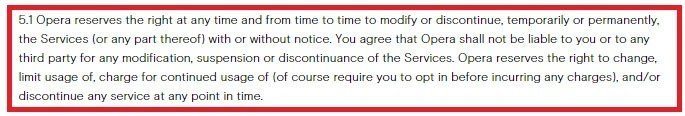

Termination clauses

Once you define what your users can and cannot do with your app, you'll want to give yourself recourse for handling violations. Including a "Termination" clause in your EULA will allow you to terminate licenses when they're abused.

Here's how Opera's EULA agreement addresses terminations:

How to link EULA in Android apps

Once you have an EULA created, you can link it to your app's profile page of Google Play Store in the same way that your other legal agreements are linked:

When a user or potential user clicks on your EULA link, he should be taken to the webpage where you host your agreement, like BitTorrent app page:

Your EULA should also be displayed within your mobile app so that after downloading and opening your app, a user can access the EULA from within the app.

This display method is also a great way to request a user accepts the terms of your EULA.

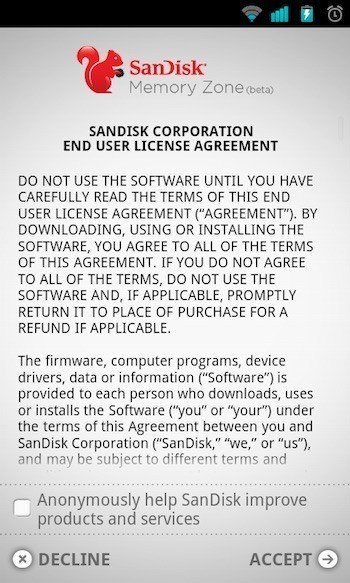

Here's how SanDisk displays its EULA within its mobile app and prompts users to accepts its terms:

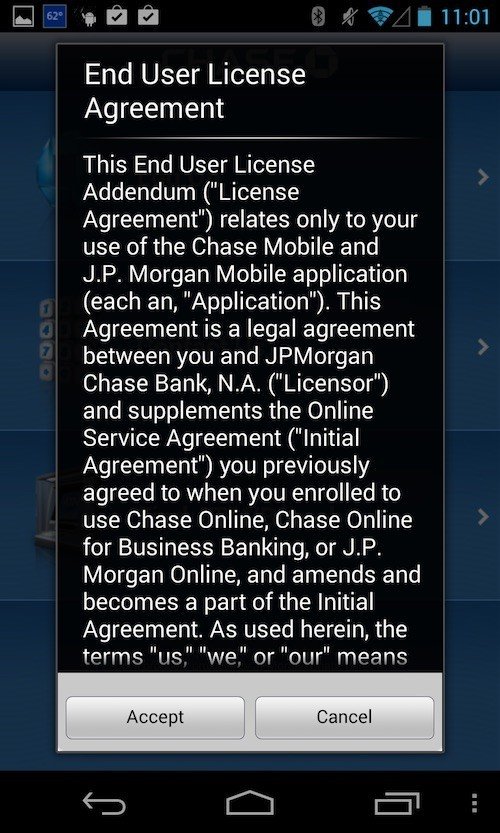

Here's another example of an EULA embedded within an Android app:

EULA vs. T&C for Android apps

Many of the same terms in an EULA can also be found in Terms & Conditions (T&C). There are developers who only have one agreement or the other and others who maintain both.

Your decision on the necessity of an EULA over a T&C for your Android app depends on the nature of your app.

First, it's a matter of user access.

An app that's downloaded on a user device is more vulnerable than one accessed through cloud services or online. A user could conceivably manipulate the code of Office 365 because most of its resources are on that user's device.

However, doing the same for a software as a service (SaaS) app that's only available online is nearly impossible--assuming you have your security protocol intact.

The downloaded app needs an EULA due to its vulnerability.

The EULA agreement grants rights for a user to operate a copy of your app after they purchase it from you. It's a specific authorization for that download and use that normally does not authorize additional activity.

The Terms and Conditions (T&C) agreement is a document that covers licensing issues but also disputes resolution provisions, payment of fees (especially with monthly subscriptions or services), and any behavior standards, such as no-tolerance policies on harassment.

If you run an online service that involves interaction between users, such as a SaaS app, you definitely need a T&C.

While an EULA will protect your interests in the software, the T&C agreement offers additional enforcement options if there is misbehavior on your app.

Basically, you need to choose the EULA and the T&C agreement based on whether you need to regulate use or behavior.

If your app requires control over both, consider drafting both a EULA and a T&C agreement.

While the default Apple's EULA offers broad protection for a variety of apps, you're not guaranteed the same kind protection if you go into the Google Play Store marketplace without your own EULA agreement.

Google Play's default provisions for Android apps offer provisions between you and the Play marketplace. Very few of them control the relationship between you and the user using your app.

That is why any developers who enter the Android market need to create their own EULA. It will preserve your intellectual property rights better and give you better tools for enforcement.