PIPEDA: Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

In June of 2015, the Digital Privacy Act (DPA) received Royal Assent and officially became law in Canada.

The Digital Privacy Act modernizes the private sector privacy laws by amending the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). This will better protect Canadian citizens' personal information when doing activities online, such as banking and shopping, and is a great step forward for Canadian privacy regulations.

Personal information includes any personal identifier such as a name, email address, telephone number, IP address, tracking of website visits through cookies placed on a user's device, GPS locations, and other information that could be used to identify someone.

Like privacy acts and laws in other countries, the DPA sets out regulations for how personal information can be collected from users, how the information can be used, and how the information can be disclosed.

It also addresses issues of mandatory notification of users in the event that user personal information collected by a website is compromised by way of a failure of a security safeguard of the website.

Main changes to PIPEDA

What does this mean for Canada-based businesses?

The three main changes to PIPEDA that the DPA makes are:

- The new graduated consent standard

- The new consent and knowledge exceptions

- The data breach notification requirement

Graduated consent required

Before the DPA became law, all that was required by a Canadian business to obtain consent to collect and use personal information from a user was that the user is clearly informed and given notice that personal information would be collected and how this information would be used.

Now, however, consent to collect a user's personal information will only be deemed as valid "if it is reasonable to expect that an individual to whom the organization's activities are directed would understand the nature, purpose, and consequences of the collection, use or disclosure of the personal information to which they are consenting."

The update to the consent requirement has been made in an attempt to protect more vulnerable groups of Canadians, such as children, and the mentally impaired.

This update means that a business is now required to make efforts to ensure that the language used to inform users is not too sophisticated for the website's audience.

For example, if your website has a very broad range of users, from adults to children, your disclosure language should be written as simply as possible to make sure that not only the adults can understand what exactly is going on.

This may be a costly and time-consuming endeavor for Canadian businesses. Because this is such a new requirement that is unique to Canada, there is no precedent and guidance is yet to be provided.

If your website caters exclusively to adults and doesn't allow children to register, you'll have a much easier time meeting this new requirement. However, if children are allowed to use and register with your website, and if anything on your website attracts or is directed towards children, you will need to significantly simplify your request for consent and your notification about data collection practices.

Authors at McCarthy Tetrault have questioned whether an organization with a website that has millions of visitors across a range of demographics would have to provide their webpage with a question about age and then, once answered, direct that individual user to one of a number of Privacy Policies.

This would take a lot of time and cost a lot of money for every Canadian website to do.

Before further guidance is published, a general way you can strive to meet DPA requirements is to simplify your Privacy Policy as much as possible.

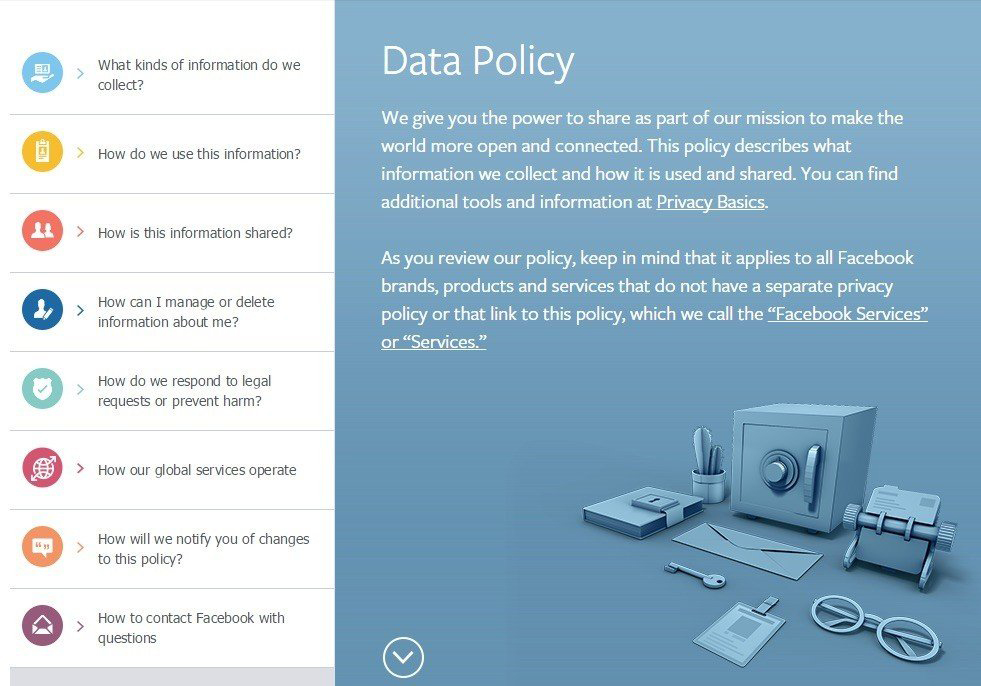

Below is an example of how Facebook has simplified a section for reading its Privacy Policy to make it easier to navigate and understand. Each section is presented as a short and simple question that a user would want the answer to, such as "What kinds of information do we collect?" and "How is this information shared?"

When one of the main questions is clicked on, a sub-menu opens with more specific breakdowns of relevant information.

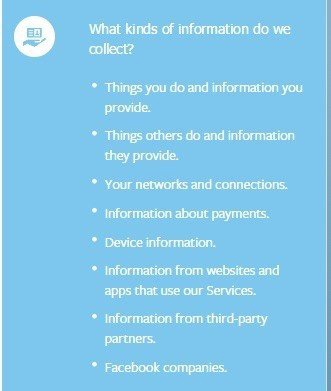

For example, when a user clicks on "What kinds of information do we collect?" he will be taken to a menu of options such as "Things you do and information you provide" and "Things others do and information they provide." This further helps a user find the exact type of information they are looking for within the Privacy Policy of Facebook.

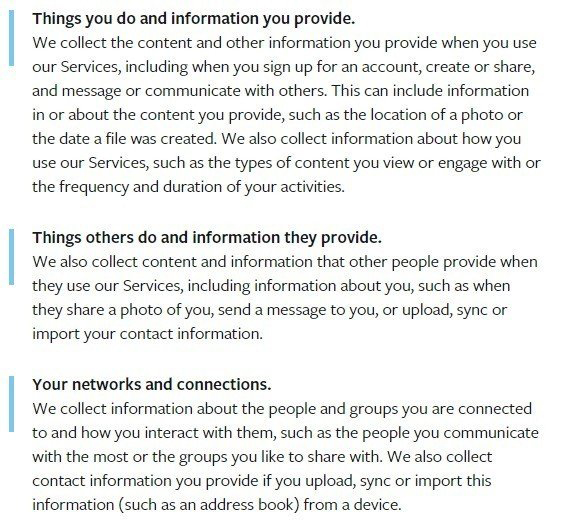

When a user clicks on one of the sub-menu options, they are taken to the relevant section where the information is written in short, clear paragraphs.

For example, Facebook lets users know that it collects information about how a user uses the service, such as the type of content viewed or engaged with, and the frequency and duration of these activities:

When a Privacy Policy is written in a very clear and easily understandable way, and access to this information is made easily accessible when requesting consent to collect personal information, the DPA should be satisfied.

When a new user signs up to use Facebook, links are provided right at the bottom of the sign-up page, and right above the Sign Up button that lets a user know, in simple language, that by clicking "Sign Up" they are agreeing to the website's legal agreements.

Each legal agreement is clearly linked back to this notice, and each legal agreement is clearly organized and written in easy to understand language:

This is an effective way to satisfy the requirements of the DPA that consent will actually be intended by the users who sign up to use Facebook.

Clear language pop-up boxes can also be an effective way of obtaining consent by providing appropriate notice.

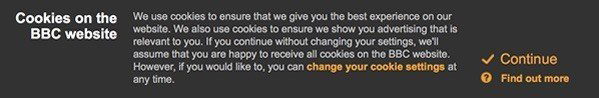

Below is an example from BBC of how the website notifies users of their use of cookies to comply with EU Cookies Directive, provides a link to "Find out more" and a link to change the cookie settings.

New consent and knowledge exceptions

A number of new and very helpful exceptions have been added for when personal information about an individual may be collected, used and disclosed without needing to provide knowledge of and obtain consent for these actions.

The key exceptions for when consent will not be required are as follows:

- When personal information is disclosed to another organization for reasonable purposes of investigating a breach of an agreement or of the laws of Canada, for the purposes of preventing, suppressing, or detecting fraudulent activity.

When personal information is used or disclosed during the course of a prospective business transaction.

Note: The information must be safeguarded during the course of the prospective business transaction, and either returned or destroyed if the transaction does not proceed as planned.

- When the personal information is produced by an employee during the course of their employment, profession, or business.

- When the personal information is information that is contained in a witness statement that is deemed to be a necessary statement to process, settle, or assess an insurance claim.

- When the personal information is disclosed by a business that has reasonable grounds to believe that the personal information is related to a breach of the laws of Canada, or the laws of a province or foreign jurisdiction.

- When the personal information is contact information that is used solely for the purpose of communicating with an individual in relation to that individual's profession, business, or employment.

Data breach notification requirement

This requirement is not fully in place yet and no timeline has been provided for its implementation. It will not be in place until the Canadian government meets with the Office of the Privacy Commission and with stakeholders to establish the specific implementation regulations. However, it is not too soon to begin considering the future requirement and how it will affect your business practices.

This requirement will, in the future, require businesses to report any and all breaches of security safeguards that involve personal information under the control of the business, if it is reasonable to believe that the security breach has created an actual risk of significant harm to an individual.

The breach must be reported to the Privacy Commissioner as well as the affected individuals as soon as feasibly possible after the breach has been determined to have occurred.

Watch for updates on this important notification requirement so you'll know when and how to begin implementation.