Apple Custom License Agreement (EULA)

When you sign-up for an Apple App Store account to distribute your app, an EULA agreement is already available for your app, even if you don't have this kind of legal agreement.

This agreement, made available by Apple for all developers, applies to apps published by developers on App Store unless the developer choose to have a custom EULA instead of the default one made available by Apple.

This is established through that Apple's default End-User Licensing Agreement (EULA) template made available for developers of iOS apps.

Why mobile apps need EULA

An EULA agreement grants users the permission to download your app on their iPhone or iPad and use the app, but never reverse engineer, copy or develop parts of the app for their personal gain. Basically, it establishes that users purchase the right to use your app without gaining any ownership interest in it.

However, this default agreement from Apple has its limitations. This EULA agreement may offer developers some protection from users who attempt to sell, redistribute or sublicense the app without any benefit to the developer but with no consideration for the specificities of developer's app or developer's industry.

Some app developers choose to include licensing clauses that are common in EULA agreements in their Terms & Conditions (T&C) (also known as Terms of Use or Terms of Service).

While this may seem like a good way to streamline 2 legal agreements into 1 single agreement, it may prevent you from being more specific as to use and termination of the license.

As a user of iOS, if an app has its own EULA agreement, you'll find it either on the developer's website or as a separate link on the app's profile page. Some developers choose to draw more attention to their EULA agreements than others.

For example, the National Basketball Association in the United States (NBA) has a lot of intellectual property it understandably wishes to protect.

When you visit its mobile app in the App Store, you'll see a link to its "Licensing Agreement" on the app's profile screen:

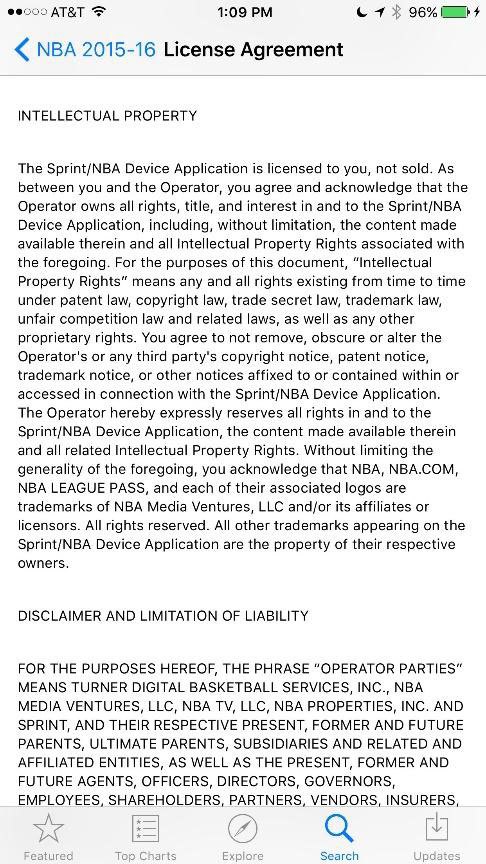

Here's the NBA's "License Agreement" text, as a user will read it:

In the NBA's license agreement, you'll find a provision on intellectual property similar to the Apple's standard EULA and its provisions.

However, you'll notice more details and clauses in the licensing agreement since the NBA owns copyrights and trademarks along with varied intellectual property including rights to broadcast games, player uniform designs, web services, apps, and other items that distinguish it from other basketball leagues.

Therefore, NBA's licensing agreement is written in a way to include all of that intellectual property, including the app itself.

A popular game in the App Store, "Fruit Ninja" is distributed by a developer called Halfbrick. When you visit the App Store to download the game you'll not see a link to its "Licensing Agreement":

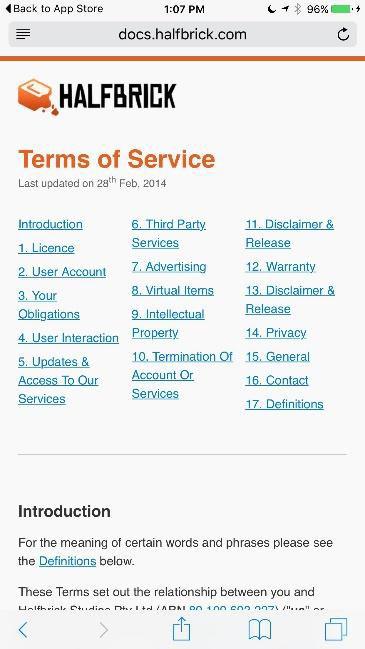

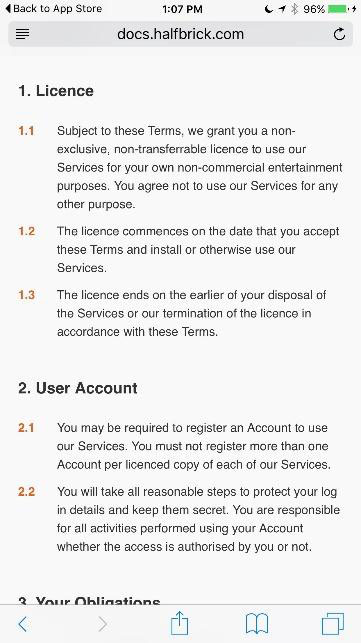

However, when you visit the Halfbrick page, you need to scroll down to the bottom of the page and visit its "Terms of Service" agreement:

The licensing provisions of the Fruit Ninja game are in this Terms of Service agreement:

This is an example of a less direct approach with EULA agreements in that the agreement is not immediately accessible but you also need to scroll a bit to find the terms.

While this takes multiple steps and appears less than convenient, it's still enough to see that Halfbrick has its own licensing terms and does not have to rely on the Apple's standard EULA:

Apps that only rely on Apple's default EULA are often one-person developers. These are normally free novelty apps that are only around a short time. They may be seasonal or their purpose is merely to test the market in order to see how an app is received.

If the app turns out to be popular, the developer may pursue a more developed version that will contain its own EULA agreement and more clauses that are customized for that particular app.

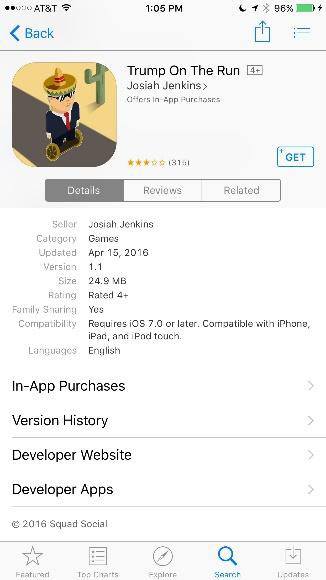

Another example here is a game available in the United States called "Trump on the Run" which is designed by Josiah Jenkins and handled by an entity called Squad Social.

It's an acknowledgment of the current election season and the humor involved will likely be outdated once all that concludes in November 2016.

The link on the app's profile screen, that says "Developer Website" only takes you to a landing page for Squad Social with no access to a Terms and Conditions agreement or an EULA agreement.

When you encounter this type of a scenario on an iOS app, Apple's standard EULA applies because the app does not provide its own legal agreements instead of the default one.

This is the landing page when you click on the "Developer Website":

Important clauses for custom EULA

When you're drafting a custom EULA agreement to replace Apple's standard agreement, your most important clauses may include any of the following:

- Authorized use of the app

- Restrictions on use

- Termination of use

- Limitation of liability

- Warranty disclaimers

Mainly, your focus needs to be on use and legal protection.

Define authorized use

Authorized use and restrictions on use are often included in the same clause or section.

This is due to the nature of EULAs: these agreements are more about what a user cannot do with the app than what users are allowed to do with it.

The latter is often very obvious just by the functions and functionality of an app. Restrictions are not always obvious and the enterprising user may take that as an opportunity to manipulate the app into an unauthorized profitable venture.

Apple's default EULA places authorized use and restrictions under a paragraph labeled "Scope of License."

This clause from Apple's contains primarily limiting provisions intended to protect the intellectual property rights of developers. The focus is on renting, leasing, selling, modifying or relicensing the app while granting the right to receive updates from the developer.

As expected, it's not specific as it needs to apply to all apps from productivity apps to games for kids:

Restrictions on Use

Like the NBA game for iOS, Microsoft is also very protective of its interests.

The Office 365 app allows for access to its Office Suite on mobile devices, including iPhone. It's also available in the Apple App Store as well.

Microsoft prefers very specific limitations to its use of Office 365 app. To access the full features of Office 365, you either need to be a subscriber to the service or intend to sign up for it in the future.

Having users mess around with the app is frowned upon by the company. Microsoft uses the legal agreement to protect its proprietary limits and if, as a user, you hacked into the app to get past this requirement, it would be a violation of the agreement, its terms, and rules.

This interest would not be represented if Microsoft defaulted to Apple's standard EULA that doesn't include this kind of clauses.

Termination of use

Termination of use clauses allows you to remove users who abuse the license of the agreement.

As expected, the Apple's default EULA is not specific. It gives just two scenarios for termination:

- A user voluntarily ends the use of an app

- Or, the developer terminates the agreement because you failed to comply with any terms of the licensing agreement.

Termination clauses do not vary as much as clauses on use or restrictions on use. That's because termination is often not an involved matter: if - as a user - you violate the terms, the access to the app is cut off.

For some purposes, it becomes more complicated than that. That when you need to give this type of clause a bit more thought.

TapeACall is an app created by Epic Enterprises that allows journalists, attorneys, and private individuals to record telephone calls for personal and professional reasons.

In the United States, there are several laws that affect the legality of recording conversations, whether they are in-person or on the telephone. Due to this, TapeACall has to take additional measures to protect itself from liability.

In TapeACall's EULA agreement, it describes particular provisions for terminating an agreement with a user, including fraud:

In this case, Apple's default EULA would not meet the particular needs of TapeACall.

If your app falls into a sector where liability is likely, take a closer and more detailed approach to your termination clauses.

Limitation of Liability and Warranties Disclaimers

Even if the clause merely addresses the possibility of software corrupting users' devices, you may also require a "Limitation of Liability" clause.

Adding a "Limitation of Liability" clause and, in some cases a "Disclaimer of warranties" clause, may give your business additional protection just in case something goes horribly wrong while your app is being used.

As expected, the provisions of Apple's standard EULA are broad waivers.

Apple's "Limitation of Liability" clause lists all causes of action, including personal injury and commercial damages, as consequences not covered by the developer of the app that uses the standard agreement instead of a custom agreement.

Apple's "Warranty Disclaimer" clause is much the same--it basically states that as a user you accept the app in "as-is" condition:

However, when you're operating in a liability-rich environment like TapeACall, these type of clauses - the Limitations of Liability and Warranty Disclaimers - must be more detailed.

When you compare TapeACall' provisions with those from the Apple's default agreement, the only similarity is that they are all written in primarily all-caps!

Here's the "Limitation of Liability" clause from TapeACall:

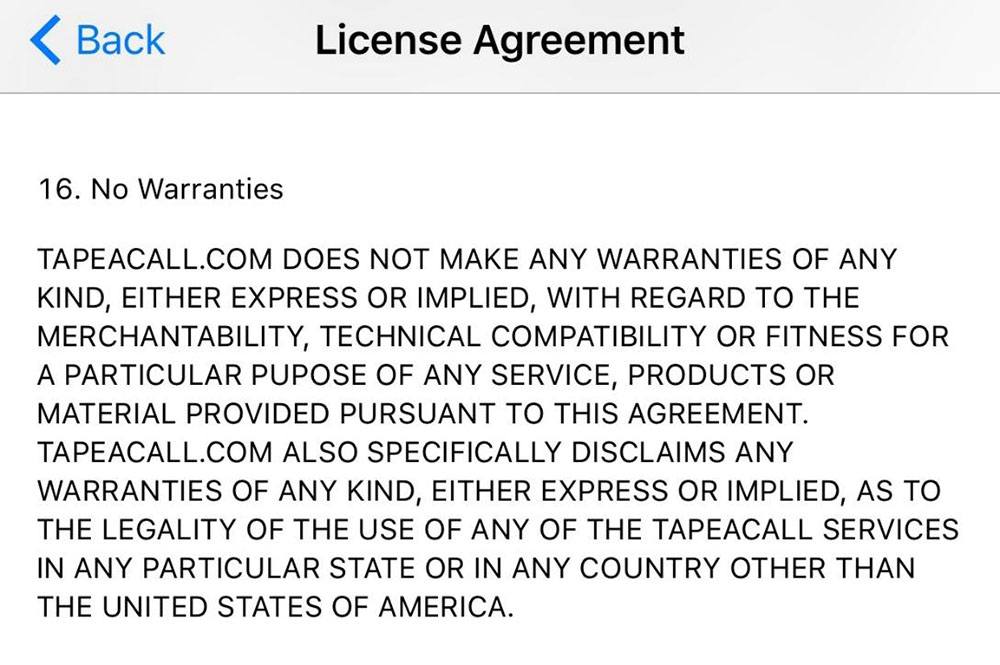

And here's the "No Warranties" clause from TapeACall:

Bottom line: customize your EULA

If the comparisons in the EULA agreements and their clauses presented above mean anything, it's the need to customize the agreement to your industry and functionality of your iOS app.

Your app could be similar to a large entity like the NBA that owns lots of intellectual property and keeps it all tightly locked. It's also possible that your app is in a test phase and you're not as concerned about its protection.

Either way, it shows that the Apple's default EULA is very limited when it comes to protecting iOS developers.

Before you release your app, consider the following:

- Is there any liability associated with its use, as with TapeACall's case explained above?If so, take extra steps to address something like this in your EULA and also in your Terms and Conditions agreement.

- Will your app involve copyrighted material like books or streaming video?If so, take steps to assure that copyright infringement is grounds for terminating the relationship.

Once you finish drafting your EULA agreement, go the direct route to inform users about this agreement by placing a link at the "Licensing Agreement" field in your App Store profile screen.